Section 1: The Vendor Credentialing Ecosystem: Market Dynamics and Key Players

Introduction: The Vendor Credentialing Imperative

In the modern healthcare landscape, vendor credentialing has evolved from an administrative task into a strategic imperative for risk management and regulatory compliance. Healthcare organizations are legally and ethically bound to ensure that every individual who enters their facilities or accesses their systems—whether a medical device representative in a sterile operating room, a pharmaceutical sales professional, an IT contractor with remote access to patient data, or a maintenance worker—is properly vetted and qualified.1 This process, known as vendor credentialing, is a critical function driven by a complex web of federal and state regulations designed to protect patient safety, safeguard protected health information (PHI) under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), and meet the stringent standards of accrediting bodies like The Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).3

The scope of credentialing is comprehensive, involving the verification of numerous data points for both vendor companies and their individual representatives. Core requirements typically include identity verification, criminal background checks, drug screenings, confirmation of necessary immunizations (e.g., influenza, MMR, COVID-19), and validation of specialized training and certifications, such as knowledge of bloodborne pathogens and HIPAA privacy rules.3 A crucial component of this process is screening against federal and state exclusion lists, such as the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General’s (OIG) List of Excluded Individuals and Entities (LEIE), to ensure the organization does not conduct business with sanctioned parties.3

The consequences of failing to maintain a robust vendor credentialing program are severe. Non-compliance can lead to substantial financial penalties, including fines from HHS, loss of accreditation, and delayed or denied reimbursements from Medicare and Medicaid.3 Beyond the direct financial impact, such failures expose the organization to significant legal liability and can cause irreparable damage to its reputation within the community it serves. Given these high stakes, healthcare providers have increasingly turned to specialized third-party Vendor Credentialing Companies (VCCs) to manage this complex and resource-intensive function.

Market Dynamics: Growth, Consolidation, and Standardization Challenges

The vendor credentialing software and services market represents a substantial and rapidly expanding segment of the healthcare IT industry. Valued at approximately USD 807.8 million in 2023, the market is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.3% to reach USD 1.42 billion by 2030.7 This expansion is primarily driven by the increasing complexity of regulatory requirements, a heightened focus on patient safety, and the operational efficiencies that specialized VCC platforms can offer to overburdened hospital administrative staff.7

A defining characteristic of the VCC market is a powerful trend toward consolidation, where larger, well-capitalized firms acquire smaller competitors to expand their network footprint and integrate credentialing into a broader suite of services.8 This consolidation mirrors similar trends observed in the wider U.S. hospital market and the Electronic Health Record (EHR) vendor market. Research shows that the hospital EHR market has moved from “competitive” to “highly concentrated,” with just two vendors, Epic and Cerner (now Oracle Health), covering over 71% of U.S. hospital beds in 2021.11 This concentration in adjacent healthcare technology sectors suggests a similar trajectory for the VCC industry, where a few dominant players control access to a vast network of healthcare facilities.

Despite this consolidation, the industry continues to struggle with a significant lack of standardization in credentialing requirements across different hospital systems.1 This fragmentation forces vendors and their representatives to navigate a patchwork of disparate policies, often requiring them to submit to multiple, duplicative background checks, drug screenings, and training modules for each new hospital system they wish to access.5 This inefficiency creates a substantial administrative and financial burden, with one industry group estimating that duplicative requirements add over $1 billion annually to the overall cost of healthcare without a corresponding benefit to patient safety.5 This dynamic places considerable pressure on vendors to comply with the demands of whichever VCC a given hospital has chosen to mandate.

The confluence of these market forces—regulatory necessity, rapid growth, and industry consolidation—has created a high-stakes “gatekeeper” dynamic. Hospitals, compelled by compliance obligations, delegate the credentialing function to a VCC. This delegation effectively grants the VCC monopolistic control over which vendors are permitted to do business with that hospital. As a VCC’s network grows through consolidation, its power as a gatekeeper is amplified, reducing choice for both hospitals and vendors and creating an environment where potentially anti-competitive or legally problematic business arrangements can take root. A vendor that objects to a VCC’s fee structure or policies may risk being locked out of a significant portion of the national market, making it exceedingly difficult to resist the terms imposed by the hospital’s chosen gatekeeper.

Profiles of Major VCCs

The vendor credentialing market is dominated by a few key players, each with a distinct market position and value proposition. The companies central to this analysis—GHX, symplr, and Green Security—represent the spectrum of business models in the industry.

GHX (and its Vendormate solution)

Global Healthcare Exchange (GHX) positions itself as the healthcare industry’s premier and longest-running trading partner network, connecting thousands of provider facilities with suppliers to streamline the entire supply chain.12 Its vendor credentialing solution, Vendormate, is integrated into a comprehensive platform that includes order automation, invoicing, payment processing, and value analysis.14 GHX’s core value proposition is the creation of a “culture of compliance” that spans its network of over 18,000 provider facilities, including more than 4,100 hospitals.13 By standardizing and automating credentialing, GHX promises to protect its clients from regulatory risk, ensure business continuity, and create safer care environments for patients and staff.14

symplr (and its IntelliCentrics/Reptrax solutions)

symplr has pursued an aggressive growth-by-acquisition strategy to become a dominant force in the broader field of healthcare operations.8 The company markets an end-to-end, cloud-based platform that addresses governance, risk, and compliance (GRC) across multiple domains, including provider data management, workforce management, and contract and supplier management.18 symplr claims that 9 out of 10 U.S. health systems use its solutions, positioning itself as the “backbone” that manages the complex, non-clinical workflows essential to running a modern healthcare enterprise.19 Its acquisition of IntelliCentrics, which itself had previously acquired RepTrax, brought a large and established vendor credentialing network under the symplr umbrella, now integrated into its expanded Access Management Solution.10

Green Security

Green Security presents itself as a more agile, innovative, and cost-effective alternative to what it terms “legacy players”.9 The company’s marketing emphasizes a customer-centric approach and a relentless focus on product innovation, contrasting this with competitors it suggests are “distracted with expanding their portfolios”.9 A central pillar of Green Security’s business model is its financial arrangement with hospitals. It explicitly advertises “no cost software” to healthcare providers, removing the need for them to source funding for a credentialing platform.23 This is made possible by a “revenue share model,” which it encourages potential hospital clients to learn about as a way to achieve cost-effective vendor credentialing.23 This model is predicated on charging fees to the vendors who are required by the hospital to use the Green Security platform.24

Section 2: Dissecting the Financial Flows: Revenue Models and Hospital Arrangements

The Standard Business Model: The Vendor-Pays System

The predominant business model across the vendor credentialing industry is a “vendor-pays” system. In this arrangement, the VCCs generate the vast majority of their revenue by charging fees directly to the third-party vendors and their individual representatives who need to access hospital facilities.24 The process is typically initiated by the hospital, which selects a VCC and then mandates that all of its current and prospective vendors register with that specific platform as a condition of doing business.26

Once this mandate is in place, the VCC collects annual subscription fees from each vendor company and, often, a separate per-representative fee for each employee who requires a credential.25 These fees cover the VCC’s costs for collecting, verifying, monitoring, and storing the required credentialing documents, such as background checks, immunization records, and training certificates.3 The fee structures can be substantial and are often tiered based on the level of access a vendor representative requires or the number of hospital systems they need to be credentialed for. For example, GHX’s Vendormate discloses a tiered pricing structure where a single representative’s annual fee can range from $290 for access to five health systems to $580 for access to 100 or more systems.25

A crucial aspect of this model is that the hospital—the entity mandating the service—typically receives the VCC’s software platform and associated management tools at little to no direct financial cost.22 The entire operational cost of the credentialing system is externalized and borne by the hospital’s supply chain partners. This creates a financial dynamic where the hospital is the VCC’s client in practice, but the vendor is the VCC’s paying customer by necessity.

Analysis of Specific Financial Arrangements with Hospital Clients

While the vendor-pays model is the standard, the specific financial arrangements between VCCs and their hospital clients vary and, in some cases, involve a direct or indirect flow of value back to the hospital. These arrangements, which include rebates, revenue sharing, and the provision of free services, are central to a legal analysis of the industry.

Rebates and Discounts (GHX)

GHX, through its integrated supply chain platform, offers financial incentives to its hospital clients in the form of rebates. The company’s ePay solution, an electronic payment processing service, is marketed to hospitals as a way to “maximize the value of your payment options” and capture significant “rebate opportunities”.29 These rebates are often linked to the hospital making early or on-time payments to its suppliers through the GHX platform.30 One GHX case study promotes the success of a health system that increased its annual rebate dollars from $65,000 to $507,000 after implementing the ePay program.30 While presented as a payment efficiency tool, this model creates a financial flow back to the hospital that is administered by the same company providing vendor credentialing and other supply chain management services.

The term “rebate” implies a return of a portion of a purchase price. However, in this complex, multi-party ecosystem, the nature of this payment requires careful examination. The hospital is not necessarily purchasing a service from GHX for which it is receiving a simple discount. Instead, it is receiving a financial benefit for utilizing a platform that its suppliers are also integrated into, often as a requirement of doing business with the hospital. The value of these rebates is a form of remuneration flowing from the VCC’s ecosystem back to the hospital.

“No Cost” Services and Explicit “Revenue Sharing” (Green Security)

Green Security’s business model is the most transparent in its financial arrangement with hospital clients. The company’s primary marketing message to providers is the availability of “No cost software,” which it positions as a key differentiator that eliminates the need for hospitals to budget for a vendor management system.23 This “free” service is a significant form of in-kind remuneration; a sophisticated, enterprise-level compliance and access management platform represents substantial value that the hospital would otherwise have to pay for.

More pointedly, Green Security explicitly invites potential hospital clients to “Learn about our revenue share model”.23 This language confirms that a portion of the revenue generated by the VCC—which comes from the mandatory fees paid by the hospital’s vendors 24—is shared directly back with the hospital. While the precise percentage or structure of this revenue share is not publicly disclosed, its existence is a core and advertised component of the company’s business model.23 This arrangement constitutes a direct cash payment from the VCC to the hospital, funded by the hospital’s own suppliers.

Explicit Revenue Sharing and Per-Visit Payments (IntelliCentrics/symplr)

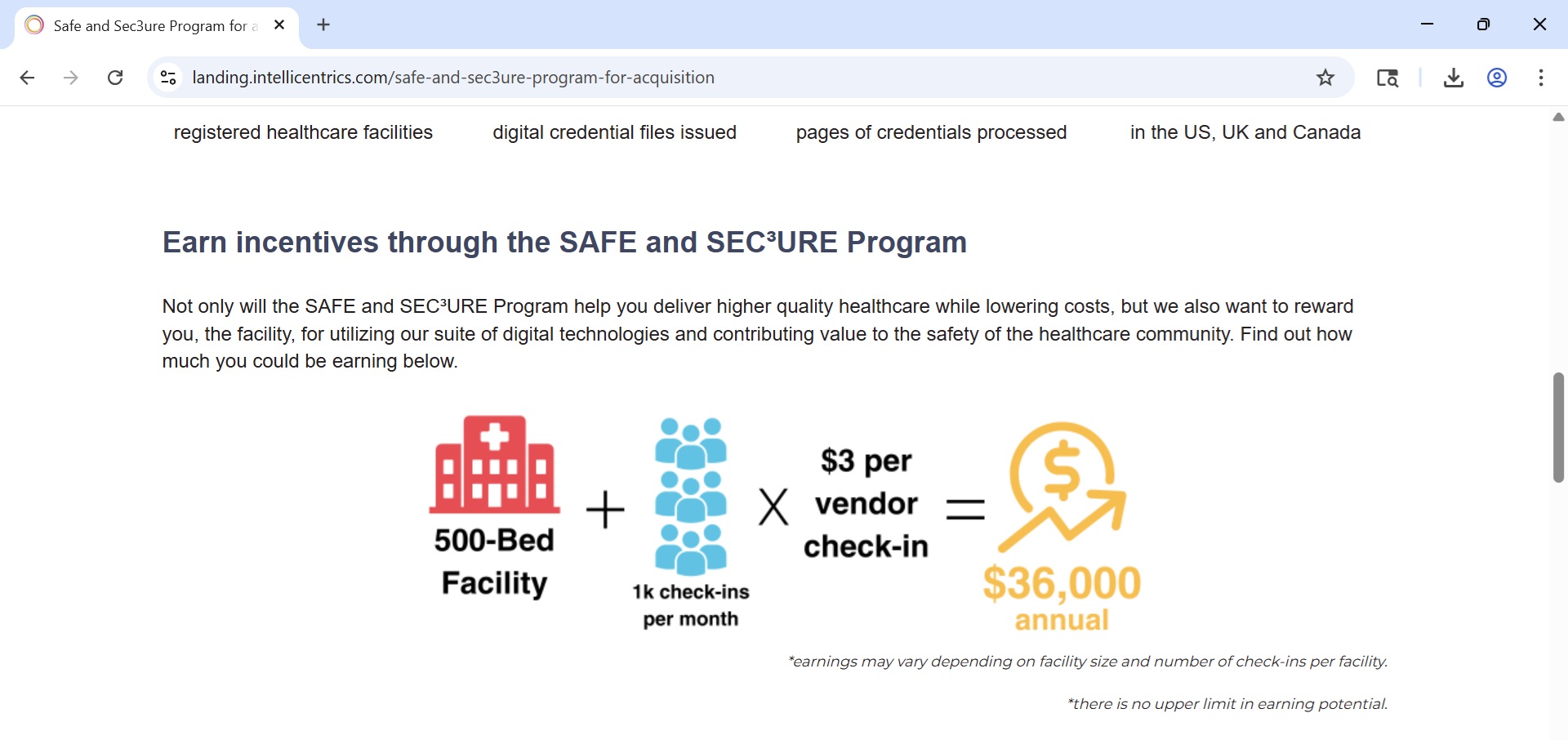

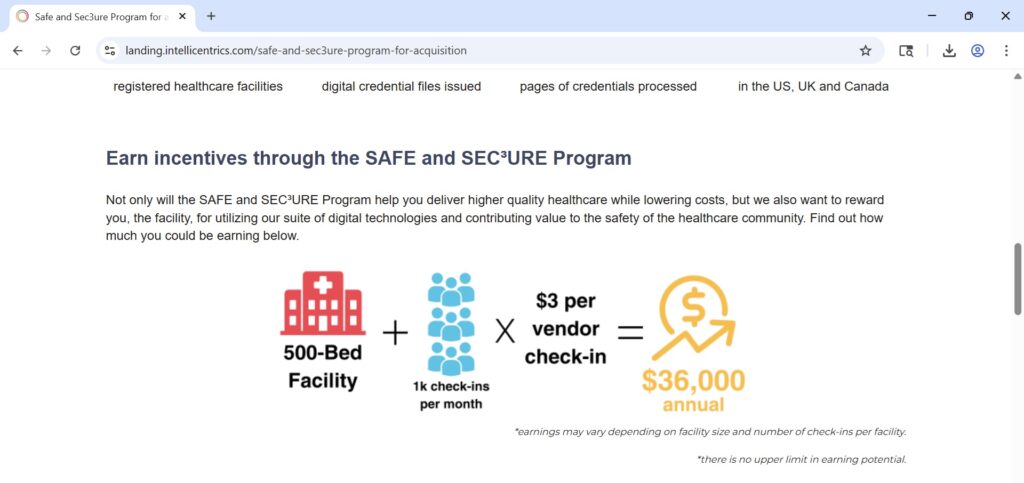

Through its acquisition of IntelliCentrics, symplr now operates a vendor credentialing platform that includes a program with explicit, direct financial payments to hospital clients. The IntelliCentrics “SAFE and SEC³URE Program” is marketed as a way to “share the financial benefits” of a secure environment with the hospitals that mandate its service.59 The terms of this program are unambiguous, offering hospitals the ability to “earn up to $3 every time a trusted and credentialed vendor representative visits your facility and 3% back on all medical credentialing and payer enrollment invoiced spend”.59

This arrangement constitutes two distinct forms of remuneration. The first is a per-visit fee paid to the hospital, directly tying the hospital’s revenue to the volume of vendor traffic it allows through the IntelliCentrics platform. The second is a straightforward rebate or revenue share based on the hospital’s spending on other credentialing services offered by the company.59 This model creates a direct financial incentive for the hospital to mandate the VCC’s use and to maximize the activities that generate payments for both the VCC and the hospital itself.59

Bundled Services and GPO Partnerships (symplr)

In addition to the direct payment models operated by its subsidiary IntelliCentrics, symplr’s broader business model presents another potentially problematic method for transferring value to hospitals. The company’s strategy is to be an all-encompassing GRC and healthcare operations platform, allowing a hospital to consolidate numerous functions—provider credentialing, vendor management, contract management, workforce scheduling, etc.—onto a single system.19 By bundling a wide array of services, it becomes difficult to ascertain the fair market value (FMV) of any single component, such as the vendor credentialing module. This creates the potential for the VCC service to be offered at a steep discount or even below cost as an inducement for the hospital to adopt the entire symplr platform, with the cost subsidized by other, more profitable service lines.

Furthermore, symplr holds a national group purchasing organization (GPO) agreement with Premier, Inc., a major healthcare improvement company with an alliance of thousands of U.S. hospitals.32 GPO contracts are a common feature of the healthcare supply chain. Under these arrangements, vendors typically pay “contract administrative fees” to the GPO based on the volume of products sold to the GPO’s member hospitals.33 A portion of these administrative fees is often shared back with the member hospitals. While this practice can be protected under a specific safe harbor to the Anti-Kickback Statute, its application in the context of a mandated service like vendor credentialing requires careful legal scrutiny.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of VCC Business Models and Financial Arrangements

| VCC | Primary Revenue Source | Stated Value Proposition to Hospitals | Known or Advertised Financial Flow to Hospital | Supporting Sources |

| GHX (Vendormate) | Annual fees paid by vendor companies and their individual representatives. | Comprehensive supply chain integration, creating a “culture of compliance,” ensuring safety and reducing business risk. | Rebates offered through its ePay electronic payment platform, often tied to early payment to suppliers. | 16 |

| symplr (IntelliCentrics) | Annual fees paid by vendor companies and their individual representatives. | End-to-end healthcare operations platform for GRC, streamlining all non-clinical workflows, serving 9/10 U.S. hospitals. | Direct payments to hospitals via the “SAFE and SEC³URE Program,” including per-visit fees and a 3% rebate on other credentialing services. Also, potential for below-market pricing through bundled services and GPO fee sharing. | 59 |

| Green Security | Annual fees paid by vendor companies and their individual representatives. | Cost-effective and innovative alternative, enterprise safety for all non-employees. | “No cost software” for the hospital and an explicit “revenue share model” where the hospital receives a portion of vendor-paid fees. | 9 |

Section 3: The Legal Gauntlet: Federal Anti-Kickback and False Claims Statutes

The business models and financial arrangements prevalent in the vendor credentialing industry operate within a highly regulated legal environment governed by powerful federal fraud and abuse laws. The two most significant statutes in this context are the federal Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS) and the False Claims Act (FCA). A thorough understanding of these laws is essential to assessing the legal risks associated with VCC payment practices.

The Federal Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS) (42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(b))

The AKS is a federal criminal law that forms the primary legal framework for analyzing the financial flows between VCCs and hospitals. The statute makes it a felony to knowingly and willfully offer, pay, solicit, or receive any remuneration to induce or reward either the referral of an individual for an item or service, or the purchasing, leasing, or ordering of any good, facility, service, or item for which payment may be made in whole or in part under a federal healthcare program, such as Medicare or Medicaid.34

A common misconception is that the AKS applies only to physicians referring patients. The statute’s language is far broader, explicitly covering remuneration intended to influence the “purchasing, leasing, or ordering” of any goods or services.34 A hospital’s decision to purchase medical devices, supplies, or pharmaceuticals from a particular vendor falls squarely within this prong of the statute. Therefore, any payment intended to influence which vendors a hospital does business with, or how it does business with them, can implicate the AKS. The statute applies with equal force to both sides of a transaction; it is illegal for a VCC to

pay a kickback and for a hospital to solicit or receive one, creating shared legal risk for all parties involved.34

“Remuneration”: An Intentionally Broad Definition

A cornerstone of the AKS is its exceptionally broad definition of “remuneration.” The term encompasses anything of value and can take any form, whether direct or indirect, overt or covert, in cash or in kind.34 This definition explicitly includes kickbacks, bribes, and rebates. Federal regulations and OIG guidance have consistently affirmed that Congress intended this definition to cover the transfer of “anything of value in any form or manner whatsoever”.34 Consequently, the financial arrangements identified in the VCC industry—including direct cash payments from a “revenue share,” transaction-based “rebates,” and the provision of valuable “no cost software”—all clearly constitute remuneration under the statute.36

The “One Purpose” Test

Federal courts have interpreted the AKS’s intent standard through the “one purpose” test. Under this standard, an arrangement is illegal if even one purpose of the remuneration is to induce or reward prohibited business, even if there are other, legitimate business purposes for the payment.38 For example, a VCC might argue that its revenue-sharing payment to a hospital is intended to foster a collaborative partnership or offset the hospital’s administrative costs. However, if another purpose of that payment is to induce the hospital to select and retain the VCC as its mandatory credentialing service—thereby generating a lucrative, captive stream of vendor fees for the VCC—the arrangement violates the statute. This test establishes a low threshold for the government to prove illegal intent.

Intent and Penalties

The AKS requires a “knowing and willful” violation. However, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 clarified that a person need not have actual knowledge of the AKS or a specific intent to commit a violation of the statute to be found guilty. The penalties for an AKS violation are severe and can be applied to both organizations and individuals. Criminal penalties include fines of up to $100,000 per violation and imprisonment for up to 10 years.34 Administrative sanctions include exclusion from participation in all federal healthcare programs—a penalty that would be catastrophic for any healthcare provider or VCC—and civil monetary penalties (CMPs) of up to $50,000 per kickback, plus three times the total amount of the remuneration involved.35

AKS Safe Harbors and Their Inapplicability

Recognizing that the AKS’s broad language could potentially criminalize legitimate and beneficial business arrangements, Congress authorized HHS to create regulatory “safe harbors” that protect certain payment practices from prosecution.36 If an arrangement fits squarely within all of the requirements of a safe harbor, it is not illegal. However, the financial arrangements between VCCs and hospitals are unlikely to qualify for protection.

For instance, the discount safe harbor protects certain price reductions but generally requires that the discount be provided to the buyer of the good or service and be properly disclosed and reported.43 In the VCC model, the hospital is not the primary buyer paying for the credentialing service; the vendor is. The value flowing to the hospital is not a discount on its own purchase but rather a share of revenue generated from a third party. Similarly, the

GPO safe harbor has specific, detailed requirements regarding written agreements and disclosures that may not be met by a typical VCC-hospital relationship, which is fundamentally about a mandated service rather than group purchasing.33 Failure to meet every element of a safe harbor does not automatically make an arrangement illegal, but it means the arrangement must be scrutinized based on its specific facts and circumstances to determine the parties’ intent.42

The False Claims Act (FCA) (31 U.S.C. §§ 3729-3733)

The FCA is the federal government’s primary civil tool for combating fraud. A crucial amendment to the AKS established a direct link between the two statutes: a claim submitted to a federal healthcare program that includes items or services resulting from a violation of the AKS constitutes a false or fraudulent claim for purposes of the FCA.34

This link has profound implications. It means that every single Medicare or Medicaid claim a hospital submits for a service or product provided by a vendor who was required to pay a fee to a VCC under an illegal kickback arrangement can be considered a false claim. This transforms the underlying criminal conduct into a source of massive civil financial liability.

Treble Damages and Penalties

The financial penalties under the FCA are draconian. A party found liable must pay up to three times the amount of damages the government sustained, plus a per-claim penalty that is adjusted annually for inflation and currently exceeds $27,000.35 In the context of a large hospital system that processes thousands of claims daily, the potential liability from an AKS-tainted vendor credentialing arrangement could easily reach hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars.

Qui Tam (Whistleblower) Provisions

Perhaps the most potent feature of the FCA is its qui tam, or whistleblower, provision. This allows a private individual (known as a “relator”) with non-public knowledge of fraud against the government to file a lawsuit on the government’s behalf.45 The Department of Justice investigates the allegations and may choose to intervene and prosecute the case. If the lawsuit is successful and the government recovers funds, the whistleblower is legally entitled to receive a share of the recovery, typically ranging from 15% to 30%.44 This financial incentive has proven to be an exceptionally powerful tool for uncovering fraud. It creates a class of potential plaintiffs—including disgruntled vendors, current or former employees of VCCs or hospitals, and even competing companies—who are highly motivated to report suspicious arrangements to the government.45

Section 4: Regulatory Scrutiny: OIG Advisory Opinions and the “Gatekeeper” Theory

Introduction to OIG Advisory Opinions

The Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General (OIG) is the primary federal agency responsible for enforcing the AKS. Through its advisory opinion process, the OIG provides guidance to the healthcare industry on whether a specific, proposed business arrangement would potentially violate fraud and abuse laws. While an advisory opinion is legally binding only on the parties that requested it, these opinions are widely regarded by the healthcare legal community as invaluable indicators of the OIG’s current enforcement priorities and analytical frameworks.49 Two recent, unfavorable advisory opinions are particularly relevant to the VCC business model, as they articulate a “gatekeeper” theory of liability that directly applies to three-party arrangements where a healthcare provider mandates the use of a third-party technology platform by its suppliers.

Deep Dive: OIG Advisory Opinion 25-08 (The Third-Party Billing Portal)

OIG Advisory Opinion 25-08, issued hypothetically on July 1, 2025, in the provided research, presents a fact pattern that is strikingly analogous to the vendor credentialing industry’s business model.50 The opinion analyzed a proposed arrangement in which a medical device company would be required by some of its hospital customers to use a specific third-party electronic billing portal to process “bill-only” invoices. Under the arrangement, the medical device company would pay the third-party portal vendor an annual fee of approximately $395 per sales representative, totaling an estimated $1.2 million per year for the company.50

The OIG issued a strongly unfavorable opinion, concluding that the arrangement would likely violate the AKS and could expose the parties to significant sanctions.49 The OIG’s analysis provides a clear roadmap for how it would likely view VCC revenue-sharing and “no cost” service models.

Factual Parallel to the VCC Model

The parallels between the arrangement in AO 25-08 and the VCC model are direct and compelling:

- Mandated Use: A healthcare provider (the hospital) requires its suppliers (the medical device company in the opinion; vendors in the VCC model) to use and pay for a specific third-party technology platform as a condition of doing business.49

- Supplier-Paid Fees: The supplier pays the third-party platform a fee for access and use of the mandated service.

- Value Flow to the Provider: The provider receives a tangible financial benefit from the arrangement. In the opinion, the OIG noted that the portal vendor advertised “potential cost savings” to its hospital clients, and the OIG concluded that the hospitals were obtaining value by mandating the portal’s use.49 This is analogous to a hospital receiving a revenue share, rebates, or free software from a VCC.

OIG’s “Gatekeeper” Analysis

The OIG’s central concern was that the arrangement could function as a mechanism to funnel a kickback from the medical device company to the hospital, with the third-party portal acting as the intermediary. The hospital, in this view, acts as a “gatekeeper” to its own lucrative business. The device company, which certified to the OIG that the portal was “redundant to [its] existing operations” and provided no “appreciable benefits,” had only one reason to pay the portal’s fees: to retain or expand its business with the hospitals that mandated its use.50

The OIG reasoned that this payment, made by the supplier to the portal vendor, could be construed as remuneration intended to influence the hospital. By mandating the portal, the hospital creates a situation where its suppliers must pay the portal vendor, which in turn provides a benefit (cost savings) to the hospital. The OIG viewed this as a suspect arrangement designed to “inappropriately steer providers” and create “anti-competitive risks”.49 The hospital’s benefit, derived from the fees paid by its supplier, could be seen as a reward for its decision to maintain the portal vendor’s lucrative position as the mandatory gatekeeper.

Analysis of OIG Advisory Opinion 25-04 (The Exclusion Screening Service)

Another recent opinion, AO 25-04, further reinforces the OIG’s skepticism of arrangements where a supplier covers a compliance-related cost for its provider customers.51 In this scenario, a medical device company proposed to pay a third-party company to perform federal healthcare program exclusion screening

on behalf of its hospital customers. The device company would pay an annual subscription fee for each customer, estimated to total $450,000 annually.52

The OIG again issued an unfavorable opinion, determining that the arrangement posed a high risk of fraud and abuse. The OIG’s key conclusion was that the device company, by paying for the exclusion screening, would be providing remuneration to its customers by “relieving [them] of this financial burden”.52 While the OIG acknowledged that exclusion screening is not technically mandated by statute, it is a critical compliance activity that providers undertake to avoid significant CMP liability. By paying for this service, the device company would be providing something of value that could “improperly sway customers toward the Requestor, especially over competitors unwilling or unable to offer similar benefits”.52

This logic applies directly to the “no cost software” model offered by VCCs like Green Security. By providing a comprehensive vendor management platform for free, the VCC is relieving the hospital of a significant administrative and compliance expense. This transfer of value, funded entirely by the fees collected from the hospital’s vendors, functions as a powerful inducement for the hospital to mandate that VCC’s service, potentially at the expense of competitors who do not offer a similar arrangement.

These recent advisory opinions demonstrate a clear and present enforcement focus on these types of three-party, technology-mediated business arrangements. The OIG is signaling that it will look past the formal structure of a transaction to scrutinize the underlying flow of funds and the intent of the parties. The lack of a legitimate, commercially reasonable business purpose for the party paying the fee (the vendor) is a significant red flag. In both AO 25-08 and in the VCC model, the vendor is often put in a position of paying a fee for a service that is duplicative, provides little direct benefit to them, and is paid solely to maintain access to the hospital’s business. This lack of fair market value exchange from the vendor’s perspective is strong evidence that the payment’s true purpose is to influence the hospital’s decision-making, which is the very conduct the AKS is designed to prevent.

Section 5: A Synthesis of Risk: Applying the Law to VCC Business Practices

By synthesizing the factual business models of VCCs with the established legal framework of the AKS, the FCA, and the analytical lens provided by recent OIG advisory opinions, a clear risk profile emerges for the financial arrangements between VCCs and their hospital clients. The core of the analysis hinges on whether the transfer of value from a VCC to a hospital constitutes prohibited remuneration intended to induce the hospital to mandate that VCC’s services for its vendors, thereby generating a captive revenue stream for the VCC.

Direct Application of the AKS and OIG Guidance

Revenue Sharing and Per-Visit Payments (High Risk)

Business models that involve explicit financial payments back to the hospital, such as the revenue-sharing model advertised by Green Security 23 and the per-visit payment and rebate program offered by symplr’s IntelliCentrics 59, present a very high risk of violating the AKS. In these arrangements, the VCC collects credentialing fees from vendors—fees that vendors are required to pay as a condition of doing business with the hospital—and then remits a portion of that revenue, or a per-transaction fee, back to the hospital.

This practice aligns almost perfectly with the high-risk “gatekeeper” fact pattern identified by the OIG in Advisory Opinion 25-08.

- Remuneration: The revenue share or per-visit payment is a direct, in-cash transfer of value to the hospital.

- Inducement: Applying the “one purpose” test, it is difficult to argue that a purpose of this payment is not to induce the hospital to select and retain the VCC as its exclusive, mandatory credentialing partner. The VCC’s entire business model depends on this mandate, and the financial payment serves as a powerful incentive for the hospital to provide it.

- Gatekeeper Theory: The hospital acts as the gatekeeper to its vendors. The payment it receives is funded by those same vendors. This creates a circular flow of funds that appears to be a classic kickback: the hospital receives a payment in return for arranging for its vendors to purchase the VCC’s services.

The IntelliCentrics “SAFE and SEC³URE Program” is a particularly clear example. By tying payments directly to vendor traffic (“up to $3 every time a… vendor representative visits”), the arrangement creates a powerful financial incentive for the hospital to maximize the number of credentialed vendor visits, which in turn generates more revenue for both the hospital and the VCC.59 This structure appears to be a textbook example of the kind of arrangement the AKS was designed to prevent: the use of financial incentives to influence healthcare business decisions, which can distort competition.59

“No Cost” Software/Services (High Risk)

The provision of a vendor credentialing platform and associated services to a hospital at no charge is a significant form of in-kind remuneration. As established in OIG Advisory Opinion 25-04, relieving a business partner of a significant operational or compliance cost that it would otherwise have to bear constitutes a transfer of value that can serve as an illegal inducement.52

- Remuneration: An enterprise-level software platform for compliance and vendor management is a valuable asset. Providing it for free relieves the hospital of a substantial expense, which is “anything of value” under the AKS.

- Inducement: The offer of “free” software is a primary marketing tool used to persuade a hospital to adopt a particular VCC’s platform.23 The implicit (and often explicit) agreement is that in exchange for the free platform, the hospital will mandate that its vendors pay the fees that generate the VCC’s revenue. This quid pro quo is strong evidence of inducement.

- Anti-Competitive Effects: As the OIG noted in AO 25-04, this practice can have anti-competitive effects by improperly swaying customers toward the VCC offering the free service, to the detriment of competitors who may offer a superior product but choose not to engage in such a high-risk business model.52

Rebates (Moderate to High Risk)

The risk associated with rebate programs, such as GHX’s ePay solution, depends critically on the structure and source of the rebate funds.29

- High-Risk Scenario: If the rebates paid to the hospital are funded, directly or indirectly, by administrative or transaction fees that GHX charges to the vendors utilizing the platform, the arrangement functions as a de facto revenue share. In this case, it carries the same high level of AKS risk, as it represents a payment to the hospital to induce the use of a platform that its suppliers must pay to use.

- Lower-Risk Scenario: If the rebates are structured as a true discount on a service that the hospital itself is purchasing from GHX, and the rebate is funded entirely from GHX’s own profit margin without being tied to fees from third-party vendors, the risk may be lower. However, even in this scenario, the arrangement would need to be carefully scrutinized to ensure it is commercially reasonable, reflects fair market value, and is not tied in any way to the volume or value of the hospital’s purchasing from vendors on the GHX network. Given the integrated nature of GHX’s platform, disentangling these elements would be a complex legal and factual task.

Table 2: Anti-Kickback Statute Risk Assessment of VCC Practices

| VCC Business Practice | Is it Remuneration? | Is there Intent to Induce? (One Purpose Test) | Does it Implicate the Gatekeeper Theory? | Potential for FCA Liability? | Overall AKS Risk Level |

| Explicit Revenue Sharing | Yes. Direct cash payment to the hospital. | Yes. Payment is a clear incentive for the hospital to mandate the VCC’s service, which is necessary for the VCC to generate revenue. | Yes. A textbook example. The hospital mandates use by vendors, and a portion of the vendor-paid fees flows back to the hospital. | Yes. All claims from vendors credentialed under this model are potentially tainted. | High |

| Per-Visit Payments & Rebates | Yes. Direct cash payments to the hospital based on vendor visits and other service spend. | Yes. Payments are explicitly tied to vendor activity and service spend, creating a direct incentive to mandate the VCC and maximize vendor traffic. | Yes. The hospital is rewarded financially for its role as gatekeeper, with payments funded by the vendors it requires to use the service. | Yes. All claims from vendors credentialed under this model are potentially tainted. | High |

| “No Cost” Software/Services | Yes. Provision of a valuable software platform and services at no charge, relieving the hospital of a significant operational expense. | Yes. The free service is the primary inducement for the hospital to mandate the VCC’s use, creating a captive market of paying vendors. | Yes. The hospital receives in-kind value in exchange for granting the VCC gatekeeper status over its vendor relationships. | Yes. All claims from vendors credentialed under this model are potentially tainted. | High |

| Transaction-Based Rebates | Yes. Cash payments or credits to the hospital. | Likely. If rebates are funded by vendor fees, the intent is to induce the hospital to use the platform, thereby generating those fees. Even if not, the rebate could induce loyalty. | Yes. If the rebate is tied to transactions with vendors who are required to use the platform, the hospital benefits from its gatekeeper role. | Yes. If the rebate scheme is found to be an illegal kickback, all related claims are potentially false. | Moderate to High |

Section 6: The Enforcement Horizon and Potential Liabilities

The legal risks inherent in certain VCC business models are not merely theoretical. The Department of Justice (DOJ) and the OIG have demonstrated a clear and increasing focus on fraud and abuse schemes that are embedded within healthcare technology platforms. Combined with the powerful financial incentives for whistleblowers, this creates a volatile enforcement environment for VCCs and their hospital partners.

Analogous Enforcement: The Practice Fusion Case

A landmark case that serves as a powerful analogue for the VCC industry is the DOJ’s $145 million settlement with Practice Fusion, an EHR vendor.54 The government alleged that Practice Fusion solicited and received nearly $1 million in kickbacks from a major opioid manufacturer. In exchange, Practice Fusion programmed its EHR software to display “clinical decision support” (CDS) alerts at the point of care, which were designed to influence physicians to prescribe the manufacturer’s extended-release opioid products.54

The Practice Fusion case is highly instructive for several reasons:

- Prosecution of a Technology Platform: It was the first criminal action against an EHR vendor and established the DOJ’s willingness to prosecute technology companies not as peripheral actors, but as central players in healthcare fraud schemes. The EHR software, like a VCC platform, was the very vehicle through which the illegal kickbacks were operationalized.

- Kickbacks to Influence Business Decisions: The scheme was not about referring patients in the traditional sense. It was about using a technology platform to influence the purchasing and prescribing decisions of healthcare providers—the same “purchasing, leasing, or ordering” prong of the AKS that is implicated by VCC models.

- False Claims Act Nexus: A significant portion of the settlement ($118.6 million) resolved civil liability under the FCA. The government alleged that every prescription resulting from the kickback-tainted CDS alerts led to a false claim being submitted to federal healthcare programs.54 This demonstrates the massive financial exposure that can result from an underlying AKS violation.

The parallels are clear: if a VCC accepts fees from vendors and provides a portion of that value back to the hospital to secure its status as the mandatory credentialing platform, it is using its technology to facilitate a financial arrangement that could improperly influence the hospital’s business decisions, thereby tainting all subsequent federally-reimbursed purchases from those vendors.

The Threat of Qui Tam Litigation

While direct government investigation is a significant threat, the most immediate and unpredictable risk for VCCs and hospitals engaged in these practices likely comes from whistleblowers filing qui tam lawsuits under the FCA.45 The structure of the VCC industry creates a wide array of potential relators who may have direct, non-public knowledge of suspect financial arrangements.

- Vendors and Suppliers: Medical device manufacturers, pharmaceutical companies, and other suppliers who are forced to pay what they perceive as exorbitant or duplicative credentialing fees are a primary source of potential whistleblowers. They have direct knowledge of the fee-for-access system and may become aware of the financial benefits flowing back to the hospital.

- VCC Employees: Employees within the sales, marketing, finance, or compliance departments of a VCC would have firsthand knowledge of how revenue-sharing or “no cost” service agreements are negotiated, structured, and marketed to hospital clients. Such individuals are ideal candidates to file a qui tam suit.47

- Hospital Employees: Staff in a hospital’s supply chain, finance, or compliance departments who are aware of and uncomfortable with the hospital receiving payments or free services from its mandated VCC could also become whistleblowers. Hospital compliance programs often encourage reporting of potential wrongdoing, which could lead to an internal investigation or an external qui tam filing.56

- Competitors: A competing VCC that loses a contract to a rival offering what it believes to be an illegal inducement (e.g., a revenue-sharing deal) could use the FCA’s qui tam provisions as a tool to challenge the practice and level the playing field.

Potential Liabilities for All Parties

The consequences of being found liable for an AKS violation, either through direct prosecution or a qui tam lawsuit, are severe for all parties involved in the arrangement.

- For Vendor Credentialing Companies: The VCC that pays the remuneration faces criminal prosecution, including fines and potential imprisonment for executives. It also faces devastating civil liability under the FCA, which could amount to treble damages on a vast number of claims, and mandatory exclusion from federal healthcare programs, which would effectively be a corporate death sentence.

- For Hospitals and Health Systems: The provider that solicits or receives the remuneration is equally culpable under the AKS and faces the same risk of criminal prosecution and exclusion. Under the FCA, the hospital would be liable for submitting the tainted claims, creating enormous financial exposure. The reputational damage from being implicated in a kickback scheme could be catastrophic.

- For Individual Executives: The AKS is not limited to corporate liability. Executives and managers at both the VCC and the hospital who knowingly and willfully devise, approve, or participate in an illegal kickback scheme can be held personally liable, facing criminal penalties including fines and jail time, as well as exclusion from the healthcare industry.40

Section 7: Conclusion and Strategic Recommendations

Summary of Findings

This analysis concludes that business models within the hospital vendor credentialing industry that involve the transfer of financial value from the VCC to its hospital clients present a high and material risk of violating the federal Anti-Kickback Statute. Practices such as explicit revenue sharing, the provision of “no cost” software and services, and certain rebate structures appear to function as remuneration paid to hospitals to induce them to mandate the use of a particular VCC’s platform. This mandate creates a captive and lucrative market for the VCC, funded by the hospital’s own suppliers.

These arrangements are structurally analogous to the “gatekeeper” fact patterns that the HHS Office of Inspector General has recently identified as high-risk in formal Advisory Opinions. By creating a circular flow of funds where a hospital benefits financially from requiring its vendors to pay a designated third party, these models corrupt the independence of the hospital’s operational and procurement decisions. Such arrangements expose all participants—the VCC paying the remuneration, the hospital receiving it, and the individual executives involved—to severe potential consequences, including criminal prosecution, massive civil penalties under the False Claims Act, and exclusion from participation in federal healthcare programs. The potent qui tam provisions of the False Claims Act create a significant and ongoing risk that these arrangements will be brought to the attention of government authorities by whistleblowers.

Actionable Recommendations for Healthcare Providers (Hospitals)

Given the significant legal exposure, healthcare providers must exercise extreme caution when contracting with VCCs. The following recommendations are intended to help hospital leadership, legal counsel, and compliance officers mitigate this risk.

- Conduct Rigorous, Multi-Disciplinary Due Diligence: The selection of a VCC should not be solely a supply chain or operational decision. Legal and compliance departments must be integral to the review, negotiation, and approval of all VCC agreements. The analysis must focus specifically on the flow of funds and value between all parties.

- Unequivocally Reject Revenue-Sharing and Profit-Sharing Models: Hospitals should not enter into any arrangement where they receive a share of the fees that a VCC collects from the hospital’s vendors. This practice represents the highest level of AKS risk and is the most difficult to defend, as it constitutes a direct cash payment in exchange for the referral of the hospital’s entire vendor network.

- Insist on Fair Market Value (FMV) for All Services Received: If a VCC provides software, administrative support, or other services directly to the hospital, the hospital must pay a commercially reasonable, fair market value price for those services. This payment severs the problematic link between the value the hospital receives and the fees paid by its vendors. The process for determining FMV should be robust and well-documented, potentially involving independent, third-party valuation experts.

- Document an Independent, Objective Business Justification: The decision to select a particular VCC must be based on legitimate, non-financial criteria. The selection process should be documented to demonstrate that the choice was driven by factors such as the quality of the VCC’s service, the robustness of its data security protocols, its network size, its operational efficiency, and its ability to meet the hospital’s specific compliance needs—not by the offer of free services or other financial inducements.

- Immediately Review All Existing VCC Agreements: Hospitals should conduct an urgent audit of their current VCC contracts. If any agreements contain the high-risk arrangements identified in this report, the hospital should immediately consult with experienced healthcare legal counsel to assess the level of risk and develop a legally sound remediation plan, which may include renegotiating or terminating the agreement.

Guidance for Industry Vendors and Suppliers

Vendors and suppliers are often caught in the middle of these arrangements, forced to pay fees to access business opportunities. They too should be aware of the legal landscape.

- Understand Your Rights and Risks: While mandatory credentialing fees are often a necessary cost of doing business, vendors should be aware that the underlying arrangement between the VCC and the hospital could be illegal.

- Utilize Compliance Hotlines and Reporting Mechanisms: If a vendor believes an arrangement is improper, it can and should use the hospital’s anonymous compliance hotline to report the concern.56 This can trigger an internal investigation by the hospital without immediate risk to the vendor’s business relationship.

- Consult with Specialized Legal Counsel: Vendors who believe they are being subjected to a potentially illegal payment scheme should consult with legal counsel specializing in the False Claims Act. Counsel can advise on the viability of a potential qui tam action, which can not only stop the fraudulent conduct but also provide a financial reward and protection against retaliation for the whistleblower.

Works cited

- Vendor Credentialing in Hospitals: A Guide for Healthcare Industry Representatives (HCIRs), accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.ghx.com/the-healthcare-hub/vendor-credentialing-guide-hcir/

- The Complete Guide to Hospital Vendor Credentialing – symplr, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.symplr.com/blog/the-complete-guide-to-hospital-vendor-credentialing

- Vendor Credentialing by State: A Complete Guide – Atlas Systems, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.atlassystems.com/blog/vendor-credentialing-by-state

- Why Vendor Credentialing is a Compliance Must-Have for Health Systems – Verisys, accessed August 1, 2025, https://verisys.com/blog/vendor-credentialing-compliance-health-systems/

- The Essentials of Healthcare Vendor Credentialing – Smartsheet, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.smartsheet.com/hospital-vendor-credentialing

- How Vendor Credentialing Mitigates Hospital Risk | symplr, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.symplr.com/blog/vendor-credentialing-an-ounce-of-prevention-is-much-better-than-the-cure

- Credentialing Software And Services In Healthcare Market Report, 2030, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/credentialing-software-services-healthcare-market-report

- Symplr 2025 Company Profile: Valuation, Funding & Investors | PitchBook, accessed August 1, 2025, https://pitchbook.com/profiles/company/54497-89

- What You Need to Know About the Vendor Credentialing Market in 2025 – Green Security, accessed August 1, 2025, https://gogreensecurity.com/blog/what-you-need-to-know-about-the-vendor-credentialing-market-in-2025

- HISTORY, REORGANIZATION AND DEVELOPMENT – HKEXnews, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www1.hkexnews.hk/listedco/listconews/sehk/2019/0327/a19071/EINTELLICENTRICS-20190314-16.PDF

- Trends in US Hospital Electronic Health Record Vendor Market Concentration, 2012–2021, accessed August 1, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10212829/

- The GHX Platform, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.ghx.com/platform/

- About – GHX, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.ghx.com/about/

- Vendor Credentialing and Compliance | GHX Vendormate, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.ghx.com/vendor-credentialing-suppliers/

- GHX: Healthcare Supply Chain Management | Materials | Inventory | SCM, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.ghx.com/

- Credentialing and Compliance for Providers – GHX, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.ghx.com/vendor-credentialing-providers/

- Vendormate Credentialing | GHX, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.ghx.com/vendor-credentialing-providers/vendormate-credentialing/

- symplr | Developing a Design System for a Healthcare Credentialing Product Suite – Crema, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.crema.us/case-study/symplr

- The Hidden Engine of Healthcare – Becker’s Hospital Review, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/strategy/the-hidden-engine-of-healthcare/

- symplr, the leader in healthcare operations, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.symplr.com/

- IntelliCentrics: Vendor Credentialing Solutions, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.intellicentrics.com/

- Why Vendor Credentialing is a Strategic Issue | HealthLeaders Media, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.healthleadersmedia.com/strategy/why-vendor-credentialing-strategic-issue?page=0%2C2

- Providers – Green Security, accessed August 1, 2025, https://gogreensecurity.com/providers

- Vendors – Green Security, accessed August 1, 2025, https://gogreensecurity.com/vendors

- FAQ | Community Memorial Healthcare, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.mycmh.org/vendor-management/faq/

- Vendor Policy | Community Memorial Healthcare, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.mycmh.org/vendor-management/vendor-policy/

- For Vendors – Texas Children’s Hospital, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.texaschildrens.org/about-us/for-vendors

- HSS Vendor Management, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.hss.edu/about/vendor-management

- ePay | GHX, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.ghx.com/invoice-and-payment-providers/epay/

- epayment strategy delivers rebate goals for healthcare provider – GHX, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.ghx.com/media/xewnx3mk/epayment-strategy-delivers-rebate-goals-for-healthcare-provider.pdf

- Contract Management Software For Healthcare – symplr, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.symplr.com/products/symplr-contract

- Premier Inc. Awards National Contract to symplr, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.symplr.com/press-releases/premier-inc-awards-national-contract-to-symplr

- GAO-12-399R, Group Purchasing Organizations: Federal Oversight and Self-Regulation, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-12-399r.pdf

- AKS – Anti Kickback Statute Explained | Whistleblower Law Collaborative, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.whistleblowerllc.com/anti-kickback-statute/

- Fraud & Abuse Laws | Office of Inspector General | Government Oversight, accessed August 1, 2025, https://oig.hhs.gov/compliance/physician-education/fraud-abuse-laws/

- Q & A: Self-Referral/Stark Law And Anti-Kickback Regulations – ASHA, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.asha.org/practice/reimbursement/medicare/qas/

- Kickback Definition, How It Works, and Examples – Investopedia, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.investopedia.com/terms/k/kickback.asp

- Patient Inducements: Law and Limits – Holland & Hart’s Health Law Blog, accessed August 1, 2025, https://hhhealthlawblog.com/patient-inducements-gifts-discounts-waiving-co-pays-free-screening-exams-etc/

- Healthcare Provider Fees May Constitute Kickbacks Even Without Direct Referrals, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.antitrustalert.com/2013/11/healthcare-provider-fees-may-constitute-kickbacks-even-without-direct-referrals/

- Anti-Kickback Training for Healthcare Professionals – The HIPAA Journal, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.hipaajournal.com/anti-kickback-training-for-healthcare-professionals/

- Stark Law / Anti-Kickback / Fraud & Abuse Lawyers – Wachler & Associates, P.C., accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.wachler.com/practice-areas/stark-law-anti-kickback-fraud-abuse-lawyers/

- General Questions Regarding Certain Fraud and Abuse Authorities, accessed August 1, 2025, https://oig.hhs.gov/faqs/general-questions-regarding-certain-fraud-and-abuse-authorities/

- White Paper: Understanding the Final Rules to Revise the Anti-Kickback Statute and Beneficiary Inducement Civil Monetary Penalty Regulations, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.dorsey.com/-/media/files/healthcare/oig-anti-kickback-statute-whitepaper-010521.pdf

- False Claims Act Information for Vendors, Contractors, Suppliers and Agents – Universal Health Services, accessed August 1, 2025, https://uhs.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/False_Claims_Act_Summary.pdf

- Colorado Healthcare Fraud Whistleblower Lawyer | Qui Tam False Claims Act Cases, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.wilhitelawfirm.com/denver/healthcare-qui-tam/

- False Claims Act “Qui Tam” Whistleblower Incentives – Katz Banks Kumin LLP, accessed August 1, 2025, https://katzbanks.com/false-claims-act-qui-tam-whistleblower-incentives/

- Qui Tam FAQs, False Claims Lawsuits and Whistleblower Guide – Getnick Law, accessed August 1, 2025, https://getnicklaw.com/whistleblowing/false-claims-act/qui-tam-faq/

- Criminal Division | Case Summaries – Department of Justice, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.justice.gov/criminal/criminal-fraud/health-care-fraud-unit/2025-national-hcf-case-summaries

- Navigating OIG’s Advisory Opinion on Medical Device Billing Arrangements and Anti-Kickback Statute Risks | ArentFox Schiff, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.afslaw.com/perspectives/health-care-counsel-blog/navigating-oigs-advisory-opinion-medical-device-billing

- OIG Advisory Opinion 25-08: Unfavorable DME – Vendor Payment …, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.bakerdonelson.com/oig-advisory-opinion-25-08-unfavorable-dme-vendor-payment-arrangement

- What’s New | Office of Inspector General | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, accessed August 1, 2025, https://oig.hhs.gov/newsroom/whats-new/index.asp

- OIG Says Medical Device Company’s Proposal to Pay for Exclusion Screening for Customers May Violate the Anti-Kickback Statute – Health Law Advisor, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.healthlawadvisor.com/oig-says-medical-device-companys-proposal-to-pay-for-exclusion-screening-for-customers-may-violate-the-anti-kickback-statute

- ePay | GHX, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.ghx.com/invoice-and-payment-suppliers/epay/

- Office of Public Affairs | Electronic Health Records Vendor to Pay …, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/pr/electronic-health-records-vendor-pay-145-million-resolve-criminal-and-civil-investigations-0

- False Claims Act Case | Whistleblower vs. Corporate Misconduct – Whitcomb Selinsky PC, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.whitcomblawpc.com/business-law-blog/false-claims-act-case-whistleblower-vs.-corporate-misconduct

- Vendor Compliance – UPMC, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.upmc.com/about/supply-chain/vendor-compliance

- For Our Vendors – Signature Healthcare, accessed August 1, 2025, https://signature-healthcare.org/about/for-our-vendors/

- symplr Contract, accessed August 1, 2025, https://www.symplr.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/symplr-Contract-Overview.pdf

- https://landing.intellicentrics.com/safe-and-sec3ure-program-for-acquisition